Posted on 9th March 2016

Observations in words and pictures by Derek McGarry, NCAD

To begin with I should declare I am not really a photographer but I am a designer. Like many designers, I enjoy taking photographs to document things I have seen in the hope that they will inspire me, or my students, to be creative in other ways. Having access to photograph the Ballymun Boiler House before it is renovated was a great chance for me add to my image database and wait for inspiration to strike.

Years ago, when I worked in the USA, I used this approach to make a series of freestanding interior lights inspired by photographs of cityscapes I had taken back at home in Belfast. These referential lights were made in combination of materials, many of which were repurposed found objects. The lights were then exhibited in art galleries and sold to collectors such as architects. I still clearly remember the thrill of selling a Harland and Wolff Goliath crane inspired light to the arts editor of the Los Angeles Times. Those were the days.

Growing up in Belfast in the 1960’s and 70’s continues to influence my interest in industrial landscapes. Belfast was not a pretty city then. It was a gritty, dirty, working city that really appealed to me.

The shipyard, docklands, linen mills and cigarette factory are particularly memorable. I’m attracted to the imposing monumental structures, with strong shapes and forms, found in industrial buildings and their equipment. Years of utility alter these environments to frequently create the most incredible surface textures and colours. These landscapes provide endless opportunity for photographers.

With its red and white striped chimney stack the Ballymun Boiler House is an established local landmark. Built in the mid-1960’s the complex ceased operation in July 2010. The building now lies derelict. It is the bit that is hidden from public view that is the most interesting to me.

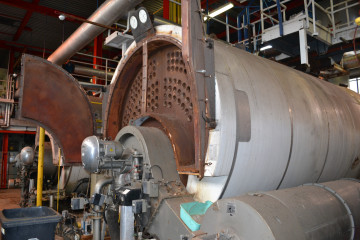

Inside the facility four massive Scotch Marine Firetube Steam Boilers now lie dormant. Fifty years ago they were a technological innovation. In their prime these powerful cylindrical oil fired central heating machines were magnificent, capable of heating over 3000 homes, schools and a swimming pool. Today they are still hugely impressive, due mainly to their scale and large footprint. As you would imagine, the boilers are no longer in pristine condition. Their once highly polished surfaces have been replaced with a vibrant palette of coloured erosion, achieved through years of community service and more recently inactivity.Each boiler was once a massive water storage tank connected to an oiled fired burner. The boilers created hot water and steam, and were fed from an underground reservoir beneath the complex. When you open their very heavy hinged smoke box doors you find row upon row of tubular steel pipes. Essentially these heat tubes once boiled the water contained inside each boiler. Now their multi-coloured surface patina patterns are extraordinarily beautiful. Flakes of rust are deposited in every nook and cranny.

Disintegrating roof panels and open windows have allowed Pigeons to naturally enhance the swatch of colours on the abandoned space and equipment. Miles of yellow and blue piping navigate their way through the red structural framework throughout the building. Painted steel gangways and staircases create the impression that you are in the boiler room of what could have been a Dutch Constructivist inspired ship. The large electrical fuse board, located below the maintenance crew’s bridge-like mission control office, is appropriately covered in breaker switches, gauges and carefully labelled signage.

Now unused and vacant the building still has numerous permanent marker references to the people that operated the facility. Whether vital instructional measurements on equipment, or personalised graffiti on lockers, these messages are evocative. Like most of the abandoned equipment it would be a shame not to preserve these symbols in some fashion.

Although a considerable logistical puzzle, the Rediscovery Centre inherits a treasure trove of potential artefacts in the making. It would be fitting if much of this waste equipment could be salvaged and reused as components in the interior and exterior design objects at the redeveloped building. Whether the approach is assemblage or maybe Steampunk, this super-salvage materials supply should be like a Lego kit for creative grown-ups. It really is a wonderful opportunity to produce something authentic. Wouldn’t made in Ballymun by Ballymun have significant impact?

Derek McGarry MFA, MA, BA (Hons), MIDI

Head of Design Innovation and Commercialisation NCAD & WISER LIFE Expert Panel Member